The semantics of buttons vs links

Senior Product Designer

In this post, we will define links and buttons, why they are not interchangeable but often misused, when to use them, and how they are affected by the additional AAA standards added in AENB77- Digital Accessibility Policy.

What is the difference between a link and a button?

A link takes you somewhere, a button performs an action. Simple right? Yet why, when you jump into the code, is it common to see a link styled as a button and a button as a link? Let’s discuss why going forward we should avoid the link-button or ‘linton’, and why they cause accessibility issues.

Semantics, Signifiers, and Affordance.

When you navigate around the physical world you interact with many doors. Some doors are pushed, some pulled, and some slide. Generally, you can predict which interaction will happen before you go through the door. But sometimes you get caught out! The door has a handle, so you pull, but it’s actually pushed. This is known as perceived affordance.

‘They may look like doors or places to push, or impediment the entry when in fact they are not.’ Don Norman UX researcher, professor, author of The Design for Everyday Things

Throughout this post I’ll continue to refer to Semantics, Signifiers, and Affordance. So we’re all on the same page, here’s the definitions I am using.

Semantics: Semantics is the study of meaning in language and the relationship between words and concepts. It is concerned with the ways in which words can be combined to create more complex meanings.

In programming, semantics refers to the meaning of code, in particular the meaning of the statements in a programming language, which can be understood by both humans and machines. In this example, semantics is important because it is the foundation of how machines understand and execute coded instructions.

Signifier:

‘Signifiers are signals. So, signifiers are signs, labels and drawing placed in the world, such as the signs labelled push, pull, or exit on doors. Any mark or sound that communicates appropriate behaviour of a person.’ - Don Norman UX researcher, professor, author of The Design for Everyday Things

Affordance: Affordances define what actions are possible.

‘An affordance is a relationship between the properties of an object and the capabilities of the agent that determine just how the object could be used. The presence of an affordance is jointly determined by the qualities of the object and the abilities of the agent that is interacting. Affordances determine what actions are possible, signifiers communicate where the action should take place.’ [1]

For example, a navigation that has a hamburger menu icon that opens only on hover. The icon signifies there is a menu, but the menu only affords mouse hover not touch or keyboard navigation.

What do doors, semantics, affordances, and signifiers, have to do with buttons and links? Buttons and links have different signifiers, user expectations, and semantics. When interacting with them we expect different interactions to happen just like in the door scenario.

What’s a button?

’A button is a widget that enables users to trigger an action or event, such as submitting a form, opening a dialog, cancelling an action, or performing a delete operation. A common convention for informing users that a button launches a dialog is to append ”…” (ellipsis) to the button label, e.g., “Save as…”.’ [2]

What’s a Link?

‘Hyperlinks are one of the most exciting innovations the Web has to offer. They’ve been a feature of the Web since the beginning and are what makes the Web a web. Hyperlinks allow us to link documents to other documents or resources, link to specific parts of documents, or make apps available at a web address.’ [3]

A button affords interaction and signifies the location of an action. For example ‘delete this item’ and has a semantic of action trigger. Buttons show :focus, :hover, :active, :disabled.

A link also affords interaction, it signifies ‘you can navigate here’ and has a semantic of linking. Links show :link, :visited, :focus, :hover, :active.

Accessibility

To make links and buttons accessible we must remind ourselves that we all consume websites differently.

Here are a few examples of how we consume websites:

- Scanning. Scan readers pick out key points from the page and then dive deeper. In eye-tracking studies, scan readers create the F pattern by scanning headings, links, and buttons. For scan readers to consume the content quickly they need to be able to identify each component out of context, using signifiers and descriptive text.

- Touch or listen. Not all of us can see websites: some of us listen or feel them. Screen readers render text and image content as speech or braille outputs. Like scan readers, screen reader users also scan by using shortcuts to bring up lists of heading, links, buttons, or key areas. When using the semantically correct code, screen readers announce the type of component.

- Screen magnifiers. Those of us with low vision can increase text sizes up to 400% and/or use magnifier software to enlarge everything on our device screen.

- Keyboard navigation. Not all of us use a mouse, cursor, or hands. Programable joysticks, buttons, arrow keys and speech recognition software such as Dragon are examples of alternatives used to navigate websites. When navigating without a cursor, focus states are used to indicate current location.

- Slow internet and limited connection. When you’re on a train, visiting friends or family, pay as you go or can’t afford high speed internet you may have experienced slow internet or limited connection. Loading a page with slow internet can be frustrating especially when you’re not expecting to move to a new page. Having the ability to reliably know that a link will reload a page and a button will not, is important for anyone with slow internet or expensive tariffs.

Thinking back to our definitions of links and buttons, have a think about how these different ways of interacting with websites can really emphasise the difference between links and buttons. For example, when using a screen magnifier clicking a link usually takes you to the top left-hand corner of a page whereas a button that deletes or open’s a modal could take you to the same location. By having the wrong semantic element or the wrong visual you could end up lost and may not be able to find your way back. A different example is a link that’s semantically a button in the middle of a table and the effort it would take to get back to where you were before.

To find out more about how we consume websites differently take a look at gov.uk’s Understanding disabilities and impairments profiles.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

AENB77 and TECH6.23 introduced 11 additional AAA WCAG Standards to our previous AA Standard at Amex. I’ve picked out WCAG standards relevant to links and buttons. If you would like to see all our AAA standards read AENB 77: Digital Accessibility Policy.

-

1.3.6 Identify Purpose Level AAA (Added in 2.1) In content implemented using markup languages, the purpose of User Interface Components, icons, and regions can be programmatically determined.

-

1.4.1 Use of Color Level A Color is not used as the only visual means of conveying information, indicating an action, prompting a response, or distinguishing a visual element.

-

1.4.3 Contrast (Minimum) Level AA The visual presentation of text and images of text has a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1, except for the following:

-

Large Text: Large-scale text and images of large-scale text have a contrast ratio of at least 3:1;

-

Incidental: Text or images of text that are part of an inactive user interface component, that are pure decoration, that are not visible to anyone, or that are part of a picture that contains significant other visual content, have no contrast requirement.

-

Logotypes: Text that is part of a logo or brand name has no contrast requirement.

-

2.4.9 Link Purpose (Link Only) Level AAA A mechanism is available to allow the purpose of each link to be identified from link text alone, except where the purpose of the link would be ambiguous to users in general.

-

3.2.4 Consistent Identification Level AA Level AA Components that have the same functionality within a set of Web pages are identified consistently.

Let’s discuss how these standards have improved our Links.

How have we changed our links?

In the DLS we have 2 types of Links:

- Standalone Text Links

- Vertical Link Lists

- Horizontal Link Lists

- Links with Icon

- Inline Text Links

Let’s take a look at links and tertiary button in V6.21.

Can you tell the difference? To quote Steve Kurg, ‘don’t make me think’. Visually there are no differences until you interact with either link or button, but for screen readers the left identifies as link and the right as a button. After the remediation here’s what a tertiary button and link look like.

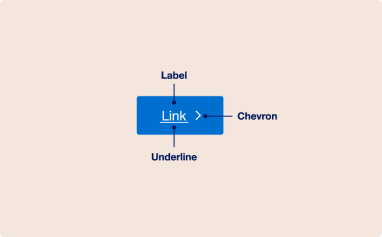

By adding the underline on default state in v6.23 there is now a visual signifier, which allows users to differentiate links from our tertiary button. Although you may not have a link and a tertiary button on the page you’ve designed, links and tertiary buttons are used across our customer journeys. The underline prevents users having the perceived affordance of an action (button).

Inline links were relying on colour as information for a signifier. Identifying colour alone doesn’t afford for colour blind or night mode. Read more in our blog post color accessibility

When should you use buttons or links?

To help you remediate your designs we have created a flow diagram of when to choose a link or button.

The first diagram is an example of the simplest way of deciding, but there are some components that can get confusing. I’ve put together a slightly more complex flow diagram for those moments.

Still not sure which component to use? Reach out to dls@aexp.com for additional guidance.

Components to watch out for:

Navigation

Although navigation uses an <a> tag, navigation is semantically different from links or buttons as <nav> surrounds the list of <a> with <nav>.

In our design system, there are enough visual signifiers to not need an underline.

Form submit buttons

Although submitting a form can change the URL, form submissions are buttons in code and should visually look like buttons.

This is an exception to the page reload rule, ‘After interacting with the component does the page reload?’. Buttons with a submit role are the semantically correct component to use. We will be going into more detail in a future blog post on forms.

But why have we not done this before?

Sadly, patterns that we see across the internet are not always accessible. For example, disabling text fields that have information that you are expected to read or a call to action styled as a button that takes you to a new page.

Here are the numbers:

- Over 90% of websites are inaccessible to people with disabilities who rely on assistive technology. (AbilityNet).

- 98.1% of home pages had detectable WCAG 2 failures (WebAIM)

- Based on a study of 1M websites by AIM, low contrast is the most common reason (86.3%) for WCAG2 failures (WebAIM)

I challenge you to question your designs. Let’s help reduce that 90%. Just because that’s how it’s always been, doesn’t mean it’s accessible. Think about how you can improve journeys for everyone - is there an alternative way?

Remember we have a new stricter accessibility policy that includes an additional 11 AAA accessibility standards. This means that something that would have been accessible two years ago in American Express potentially is no longer accessible.

Feedback

The team and I went through a year of remediation and learned a LOT along the way. We want to hear from you! Are you excited about accessibility or have questions about the impact on your team’s work? Let us know on slack or by emailing dls@aexp.com.

[1] What Are Affordances? | IxDF (interaction-design.com)

[3] Creating hyperlinks - Learn web development | MDN (mozilla.org)

Questions?

Connect with the DLS Team on Slack or by email.

Resources

Check out additional resources.